🇧🇿 What Was British Honduras?

Before we were Belize, we were named by others. But our roots ran deeper than any border, flag, or stamp.

A Name That Wasn’t Ours

For nearly 111 years, the land we now call Belize was known to the world as British Honduras. It was a name that didn’t come from the rivers, reefs, or Maya mountains. It came from the British Crown.

And while the world stamped that name on maps, flags, and passports, we lived something else. Our story wasn’t written in colonial ink. It was carried in memory, culture, and resistance.

Today, few people—even Belizeans—truly know what British Honduras was. But if you’ve ever heard your grandmother say it… or seen it on an old passport… or wondered why Belize feels invisible in world history… this is where the story opens.

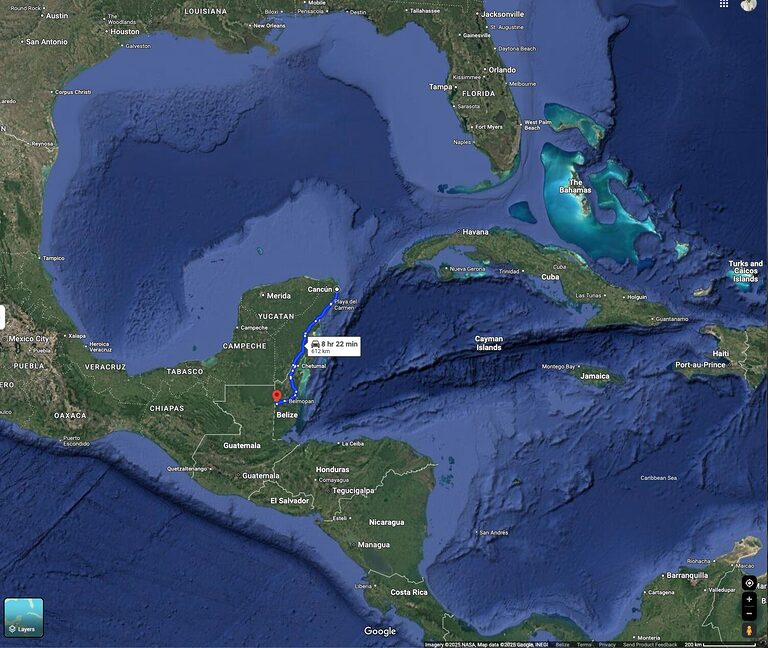

The name British Honduras came from the Bay of Honduras in the Caribbean Sea, the large gulf that stretches along the coasts of Belize, Honduras, and Guatemala. Early British settlers and logwood cutters used this bay as their point of entry into the region, and the colonial authorities adopted the geographic reference for the settlement. By attaching “British” to “Honduras,” the colony was distinguished from the neighboring Spanish-ruled Honduras on the mainland.

📍 What (and Where) Was British Honduras?

British Honduras was a British Crown Colony from 1862 to 1973, occupying the same land that Belize does today. But its existence started even earlier:

- 1600s–1700s: British logwood cutters (Baymen) settled near the coast, mostly around present-day Belize City.

- 1783–1786: Britain formalized control through treaties with Spain (Treaty of Versailles, Convention of London)—not because Spain gave up, but because the British agreed not to expand further inland.

- 1862: The settlement was officially declared a British Crown Colony and named British Honduras.

- 1973: The name changed to Belize, ahead of full independence in 1981.

🏴 Symbols of Colonial Identity

1. The Flag of British Honduras

From 1919 to 1981, British Honduras flew a Blue Ensign with a local badge—featuring two men cutting wood. Even the flag centered extractive labor.

2. British Honduras Passport

Issued until the early 1970s, this passport listed your nationality as a British subject, not Belizean.

📜 Why Did the British Want Belize?

One word: timber.

First it was logwood (for European dyes). Then mahogany, harvested inland by enslaved Africans and later by Maya and Creole workers. The British weren’t interested in creating a nation—only in resource extraction.

So why did they stay?

Because the land was rich, and the rivers were ready to carry it all to the sea.

🪵 This is why so many of Belize’s old towns like Monkey River, Boom, and Gales Point were placed along rivers—not for beauty, but for timber transport.

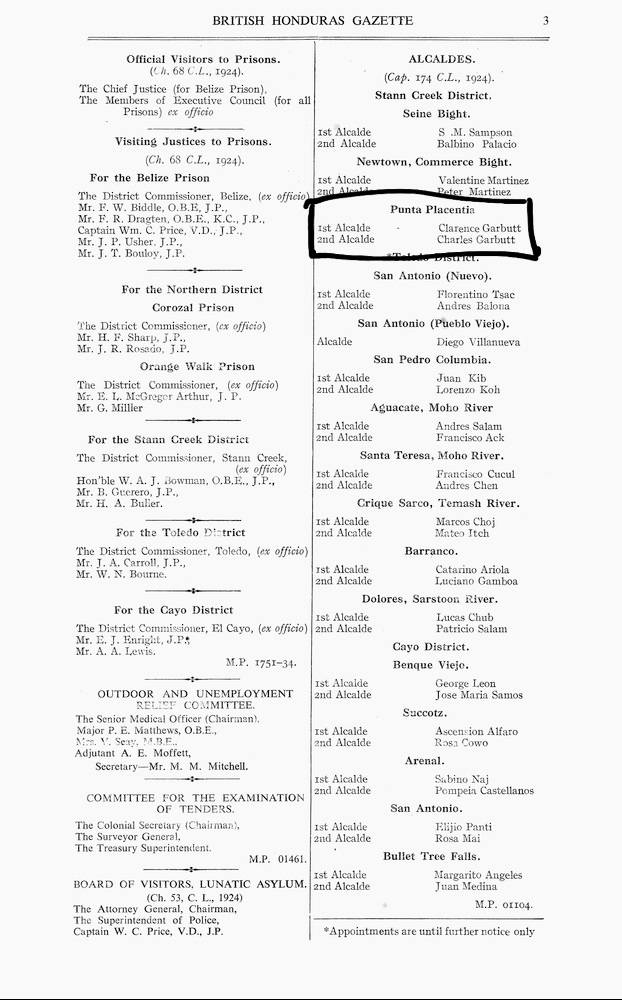

🧬 British Honduras in My Family’s Memory

My aunts, uncles, and grandparents were born under the name British Honduras.

They walked through colonial towns, attended Anglican schools, and held passports that didn’t say “Belize.”

But even then, they knew who they were. The name wasn’t their identity. The land was.

When they moved between Monkey River, Placencia, and Belize City, they weren’t crossing borders—they were carrying stories. My bloodline carries that same movement.

And I still meet elders today who say “I was born in British Honduras”—with a strange mix of pride and pain.

🧭 The British Presence After the Name Change

The name British Honduras officially ended in 1973, but Britain’s shadow did not vanish with the new word “Belize.” Even after independence in 1981, the presence of British figures, legacies, and power remained woven into the land.

One of the most enduring reminders is Baron Bliss, an Englishman who never set foot on Belizean soil, yet left nearly his entire fortune to the colony upon his death in 1926. His trust fund still supports community projects today, and every March 9th Belize observes Baron Bliss Day in his memory — a sign that colonial ties were not only political, but personal and philanthropic.

In 1994, more than a decade after independence, Queen Elizabeth II visited Belize. The visit was symbolic: the monarch who once reigned over British Honduras was now a guest in Belize — still respected, but no longer sovereign. It was a moment that captured the country’s transition from colony to nation, balancing respect for its history with the pride of self-determination.

And it is worth remembering: not all the British left. Many families stayed, continuing as part of Belize’s social and economic life. Their children attended local schools, bought land, and built businesses. Some integrated into the Creole, Mestizo, or Garifuna communities, while others maintained distinct enclaves. The colonial rulers became neighbors, sometimes even kin, in the small fabric of Belizean society.

The legacy of British Honduras, then, is not only in the name. It is in the institutions, philanthropy, and families that remained, and in the ways Belize absorbed, resisted, and reshaped that inheritance into its own identity.

🧭 Why So Few People Know This Name Today

Here’s the quiet truth:

Most of the world still doesn’t know where Belize is.

And even fewer know that it was once British Honduras.

That disconnect matters. It explains why Belize is often:

- Left off Caribbean maps

- Mistaken as an island

- Misunderstood as Spanish-speaking

- Ignored in major tourism rankings

But reclaiming the full timeline of our name is how we reclaim place, presence, and pride.

📆 Timeline of the Name

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1783 | Treaty of Versailles: Spain recognizes British logging rights |

| 1862 | British Honduras declared a British Crown Colony |

| 1964 | Self-government begins under British rule |

| 1973 | Name officially changed to Belize |

| 1981 | Full Independence |

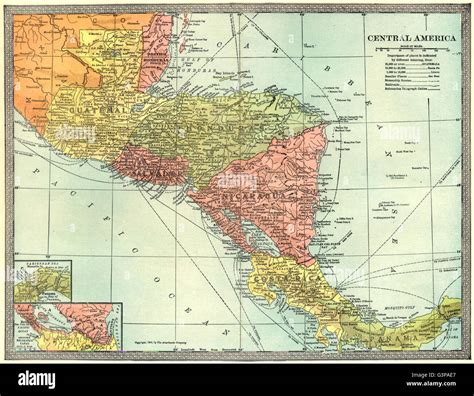

Map of British Honduras (1862–1973):

🌎 How This Compares to Other Countries

Most Caribbean or Central American countries had consistent or pre-colonial names:

| Country | Colonial Name | Independence or Renaming |

|---|---|---|

| Belize | British Honduras | 1981 (name changed 1973) |

| Jamaica | Jamaica (under British rule) | 1962 |

| Barbados | Barbados (under British rule) | 1966 |

| Guyana | British Guiana | 1966 |

| Bahamas | Bahamas (British) | 1973 |

| Suriname | Dutch Guiana | 1975 |

| Trinidad & Tobago | Trinidad and Tobago (British) | 1962 |

| Saint Lucia | Alternated French/British | 1979 |

| Grenada | Grenada (British) | 1974 |

| Honduras | Spanish Honduras | 1838 |

| Guatemala | Spanish colony | 1821 |

| Nicaragua | Spanish colony | 1821 |

| Mexico | New Spain | 1821 |

Notice how Belize was one of the last mainland territories still carrying a colonial name into the 1970s.

🔗 Why This Matters for Your Journey

If you’re reading this, maybe you’re planning a visit…

Or maybe you’re Belizean, trying to understand your roots…

But either way, I want you to know:

British Honduras wasn’t the beginning of Belize.

And Belize wasn’t the end of that story—it was the name we chose for ourselves.

📚 Citations

- British Honduras colonial flag history: Wikipedia

- Passport example: Reddit

- Timeline of British rule: Encyclopedia Britannica

- Colonial map archives: The Map House (RGS, 1927)

- Name change context: National Symbols of Belize