Hurricane Categories and What They Mean for Belize

Hurricanes in the Caribbean

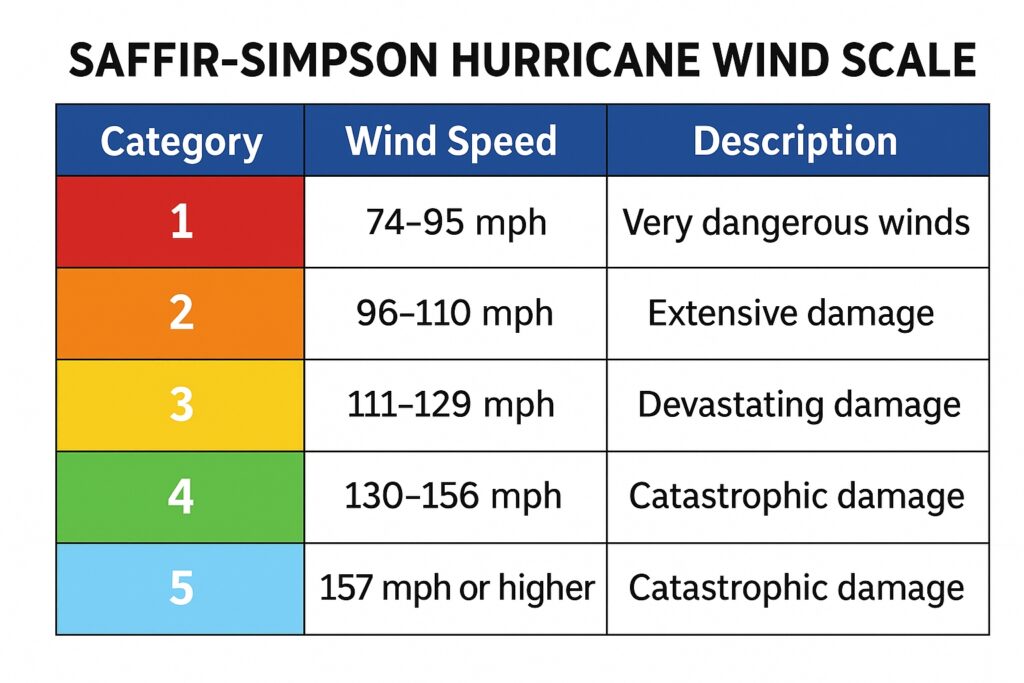

Hurricanes are part of life in the Caribbean. They are measured on the Saffir–Simpson scale, which ranks storms from Category 1 to Category 5 based only on maximum sustained wind speed. This gives a sense of wind strength, but it doesn’t tell the full story of what a storm means for Belize.

- Category 1 (74–95 mph / 119–153 km/h) – Minimal damage, though power outages and tree damage are common.

- Category 2 (96–110 mph / 154–177 km/h) – Moderate damage. Roofs and windows may be damaged, flooding increases.

- Category 3 (111–129 mph / 178–208 km/h) – Major damage. This is considered a “major hurricane.” Structural damage is possible.

- Category 4 (130–156 mph / 209–251 km/h) – Severe damage. Trees are uprooted, power poles down, large areas evacuated.

- Category 5 (157+ mph / 252+ km/h) – Catastrophic. Buildings destroyed, areas left uninhabitable. Hurricane Hattie (1961) struck Belize as a Category 5, destroying Belize City and forcing the move of the capital to Belmopan.

The scale is helpful, but it’s only one piece of the picture.

Hurricane Categories Across the Hurricane Belt

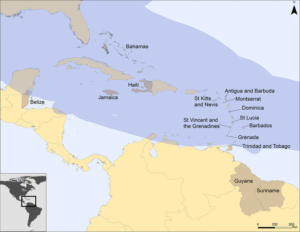

The hurricane belt stretches from the west coast of Africa across the Atlantic, through the Lesser Antilles, across the Caribbean Sea, and into the Gulf of Mexico and the U.S. mainland. Storm categories may be the same everywhere, but their impacts differ by region:

- Caribbean Islands – Small islands like Barbuda, Dominica, Puerto Rico, and the Bahamas often feel the full force of a storm, no matter its size. A Category 1 storm that might cause limited damage in a larger country can disrupt entire islands here. Category 4 and 5 storms, like Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico (2017) or Dorian in the Bahamas (2019), left catastrophic destruction because there was nowhere for people to move inland.

- United States – Hurricanes that make landfall in the U.S., especially along the Gulf Coast and Florida, often strike larger landmasses with more evacuation routes. Categories matter here because wide coastal populations are exposed — a Category 2 storm in Louisiana can cause billions in damage due to infrastructure density, while a similar storm in Belize might primarily affect one district.

- Belize and the Western Caribbean – Because Belize sits on the western edge of the belt, we experience fewer direct hits than eastern islands. When storms do reach us, they are often compact late-season systems. This is why a Category 1 or 2 can feel intense locally, while larger storms usually weaken or curve away before hitting our coast.

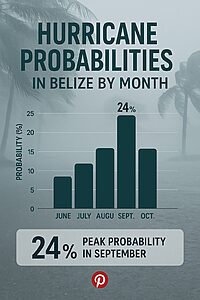

Learn more about the Caribbean Hurricane Season

Fact: Hurricanes aren’t all the same size. Some cover hundreds of miles; others, like Iris in 2001, were small but intense, striking just one narrow corridor of Belize

Why the Same Category Feels Different

The number on the scale doesn’t tell the whole story. A Category 3 storm in Puerto Rico is not the same as a Category 3 in Belize or Florida. The island’s size, the population density, and the ability to move inland all change the outcome.

That’s why in Belize, we don’t just look at the category. We watch the storm’s speed, size, and track — and prepare based on how those factors interact with our geography.

How I Look at Hurricanes in Belize

After living through storms here, I’ve learned to watch three things — and wind is the last of them.

- Forward Speed

* A storm that moves slowly or stalls can drop enormous rainfall, flooding rivers and towns even if its winds aren’t extreme.

* Hurricanes like Mitch (1998) and Eta (2020) showed how deadly slow-moving storms can be for Central America and Belize. - Size

* Large hurricanes spread rain, surge, and wind across wide areas.

* Compact hurricanes may be intense but affect only a narrow corridor.

* Hurricane Iris (2001) was a small but powerful storm that devastated Placencia, Monkey River, and Independence — yet much of Belize was untouched. - Wind

* Wind destroys trees and damages buildings, but in Belize, storms are often small and compact, meaning wind damage is concentrated.

* Hurricane Lisa (2022) was only a Category 1, but it hit Belize City directly and left widespread flooding and damage there, while southern Belize saw little impact.

So when I hear a storm warning, I don’t just ask “What category is it?” I ask:

- How fast is it moving?

- How big is it?

- Where might it stall?

That’s the difference between a storm that passes quickly with little disruption, and one that floods half the country.

Belize’s Size and Storm Impact

To understand hurricanes here, you also need to picture Belize’s geography:

- From north to south, Belize is about 170 miles (274 km).

- From east to west, it’s about 68 miles (109 km) at its widest.

This means a compact storm can devastate one region while leaving the rest of the country almost untouched. A big, slow-moving storm could cover nearly all of Belize at once. Our small size explains why hurricanes feel so different here compared to the larger islands of the Caribbean.

Tourism Destinations and Hurricane Risk

Belize’s top coastal destinations are always mindful of the season:

- Ambergris Caye – The largest island and most visited destination, located off the northern coast. While less frequently hit, its position on the barrier reef means storm surge and flooding are always concerns. Resorts here have well-established evacuation plans to move guests inland if needed.

- Placencia – A narrow peninsula in southern Belize, Placencia was devastated by Hurricane Iris (2001), which showed how compact storms can cause extreme local damage. Today, hurricane protocols are built into every resort’s emergency planning.

- Hopkins – This Garifuna village and growing tourism hub in Stann Creek District lies on the coast but with quick access inland. Like Placencia, it is vulnerable to coastal flooding, but its community-based tourism makes relocation and preparedness easier to manage.

These destinations are beautiful, but their safety depends on the same factors as the rest of the country: storm speed, size, and track. Visitors should know that all resorts and tour operators follow the official flag system and NEMO guidance, ensuring guest safety is the top priority.

Living With Hurricanes in Belize

No matter the category, two things are certain:

- Wind will topple trees.

- Rain will cause flooding.

Belizeans have learned to adapt. The Cayo District, the valleys of Stann Creek, and the interior of Toledo are trusted shelter zones, far from the surge of the coast. The next priority is always a sturdy roof — strong enough to hold through pounding rain and wind.

On the coast, fishermen move their boats into mangrove channels, where the roots shield them from waves no matter what category approaches. Offshore, storms often bring different effects. A hurricane that hit Corozal recently brought only rain and high winds to Long Caye on Lighthouse Reef, where the Blue Hole lies. Out there, the wind did little damage — and the rain was even welcome.

This is the Belizean way: we know the winds will blow and the rivers will rise, but we also know where to move, how to prepare, and how to recover. Hurricanes are part of our rhythm with the Caribbean Sea — a rhythm of respect, resilience, and survival.